Brexit cut UK passport perks but did it boost real power? From tax breaks abroad to unexpected prestige in immigration lines, the truth is far stranger than the doom-mongers predicted.

Alexander Francis Shaw

Mar 2, 2025 - 11:50 AM

Share

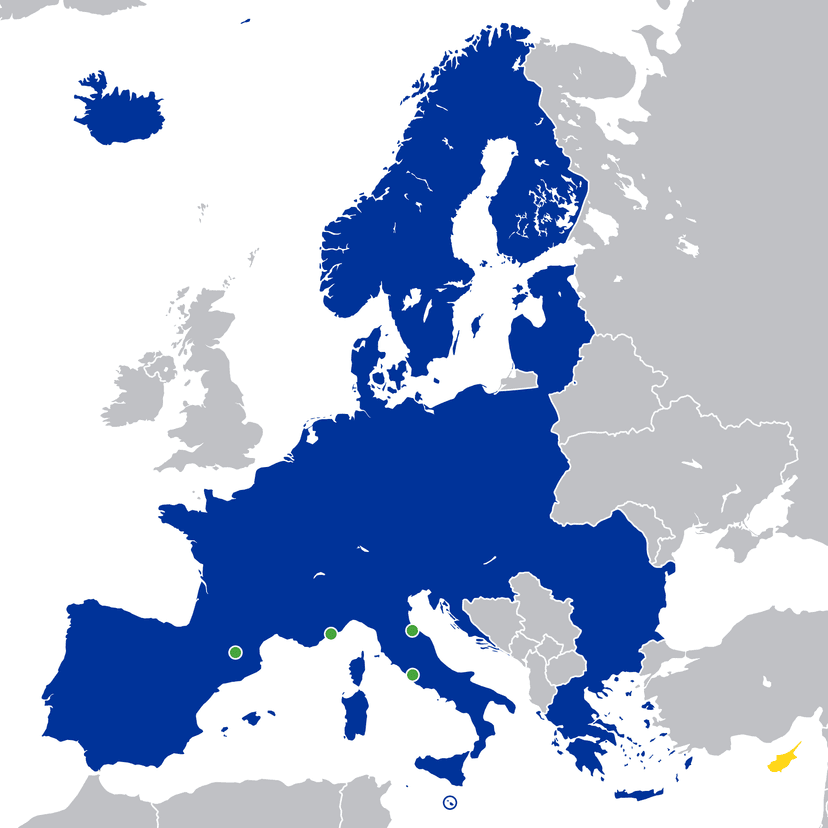

Previously, UK citizens could travel freely across the Schengen Zone, the bulk of the European Union operating under a shared border regime. Now they are bound by the familiar formula: “90 days in every 180.” To help travellers, the European Commission even provides a handy calculator.

Some argue that Britain’s “passport power”, and by extension, its national dignity is in rapid decline. That view is short-sighted.

On 1 February 2020, I watched the European Union flag lowered over Gibraltar. Back in Britain, many of my friends — including a prominent Tory MEP who had campaigned hard for Brexit — were already scrambling to obtain Irish passports. These so-called “Plastic Paddies” believe that dual nationality preserves their European identity. But there’s a flaw in that assumption.

Today, several struggling Mediterranean economies are rushing to offer “Digital Nomad Visas,” allowing foreigners to bring their incomes to their shores for extended periods. UK citizens can now live, work, and earn abroad in ways that were not possible before Brexit. The specifics vary by country, but the real kicker is that these schemes are not available to EU citizens, who must continue to pay EU taxes.

For example, UK remote workers can now live in Spain and obtain residency for five years or more, paying just 15 percent tax. However, I would argue that even this misses the point of Brexit and what people truly believed they were voting for.

Gibraltar, a tiny UK territory at the southern tip of Spain, voted 95% to remain in the EU. But raw data can be a deceptive measure of human behavior. Given Spain’s post-Brexit attempts to strong-arm Gibraltar, that number is almost certainly lower now, not higher.

The further people are from the frontiers of reality, or perhaps, the reality of frontiers, the more they cling to data-driven misconceptions about free movement and “passport power.” For diehard Remain voters, foreign policy is often a matter of economic triage, where frills like “sovereignty” shouldn’t get in the way of practical sense. This leaves Brexiteers hard-pressed to explain that threats of ostracism from both the UK Remain lobby and the EU, however mild, were part of the reason for Brexit in the first place, rather than a deterrent. As it turns out, those threats may also have been rather shallow.

So, I’d like to offer some anecdotal perspective on the ins and outs (that is, entries and exits) of Europe without an EU passport.

I am a sea captain. In the first year of British independence, few people travelled anywhere due to the COVID phenomenon. A ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy was applied to air and sea crews, who could not be expected to be fully vaccinated and boosted to every standard required by every jurisdiction they visited. This attitude soon spread to passport controls. Indeed, the absurdity of upholding officialdom for the few legitimate arrivals at Italian seaports must have rankled, because many ports laid off their customs staff entirely. I entered and exited multiple times without being stamped in or out at all.

Yet I was assured by people in London—many of whom had barely stepped outside their houses, or the echo chamber of the long-defeated Remain movement—that things were about to get worse:

“As the reality of Brexit bites and international travel increases post-lockdown, Britons are about to find out a few things about border privilege – namely, what happens when you lose it. Only a nation that viewed freedom of travel as an entitlement could have thrown it away so breezily. Those who did not grow up with border privilege can tell you that without it travel is an obstacle course; something you gird your loins for, prepare dossiers of documents for, say several hail Marys and inshallahs for.”

Nesrine Malik, Guardian, 2022.

In 2023, when things had returned to normal, I ended up overstaying my Schengen welcome due to necessary boat repairs in Ermopoli. I avoided trouble by sailing to Turkey without stamping out, thus becoming one of the 60,000 illegal migrants who crossed the Aegean Sea that year (albeit in the atypical direction). I don’t expect the other 59,999 faced much stronger consequences than I did.

But, speaking of desperate migration, there’s another, completely intangible measure of ‘passport power’ that I must mention. It was revealed to me on a recent flight from Tirana to Rome.

Albania is one of the poorest countries in Europe and is not in the EU. After their ghastly communist regime fell, they broke records for migration numbers. A third of native Albanians now live abroad. Britain is seen as the prime destination for those of a particular entrepreneurial spirit, but for honest hard workers, Italy is good enough.

I arrived at Rome Airport with a planeload of perfectly decent Albanians, whose demeanour, patience, and queue discipline were nothing that any Italian could complain about.

There were also a few Italians on the flight, easily identified by their brighter clothing and slightly superior bearing. They were ushered through the ‘EU/EEA’ passport control kiosk, while the rest of us shuffled slowly forward in the ‘Non-UE/Altri Paesi’ queue.

The minutes ticked by. The woman at the front of our line carried a baby on each hip and appeared to be having difficulty explaining that her children, too, had a right to enter Italy. This was the last inbound flight of the evening, and the passport control staff couldn’t finish their shift until everyone had been processed. Having cleared the Italians, they then started finding ways to use the redundant second desk. A Capo appeared and walked up the line.

“Qualcuno con un permesso di soggiorno?”

A few dozen Albanians with settled status in Italy were now allowed into the fast queue.

Sheep separated from goats. The ‘Non-UE/Altri Paesi’ queue shuffled forward, chastened, I sensed, by a collective sense of inferior ‘passport power.’ At the front, a bricklayer was now trying to provide evidence of employment. The fast queue had again diminished, and the Capo was coming back up the line.

“Sposi Italiani?”

The husbands and wives of Italian citizens were now ducked under the barrier, leaving me standing among a crowd who were, shall we say, Albanian even by Albanian standards: about fifty people of shaky, unsettled status, awaiting judgment in the hope of being cleared into a world of manual labour under the harsh Etruscan sun. And me—clean-shaven, in a Barbour jacket.

The Capo came back up the line for a third time, his eye fixed on the anomaly. Had a white Rajah slipped in among the aboriginals? Perhaps he spied the burgundy back cover of my pre-Brexit passport, because he now addressed me, sotto voce, in person.

“Ma lei Italiano?”

My neighbours also showed curiosity. The moment had arrived to flex the transcendent ‘power’ of the UK passport. Mustering all the camp indignation I could, I flourished the embossed Lion and Unicorn crest at him and declared:

“No, cavaliere! Sono Britannico!”

I would be lying if I said my flat-capped and Shayla’d queue-mates burst into applause, but it seemed as if the collective dignity of the ‘Non-UE/Altri Paesi’ queue had, in that moment, risen considerably. Don Brexite stood firm in solidarity among his fellow pilgrims—Laurence of Albania, Drake of Dürres—and felt a stirring of the crowd which, in 52% of British hearts on 23 June 2016, had sounded the trumpets at Jericho. Did the airport police brace their haunches just a little at the sight of our lifted spirits? Did they push me into the fast queue, for fear that the spirit of rebellion might spread to the masses?

This is the real reason I feel sorry for those who whinge about ‘Britain’s reduced status.’ They just don’t understand that power lies where men believe it lies. They should ask not what their ‘passport power’ can do for them, but what their ‘passport power’ can do for the spirits of a hundred depressed Albanians in an airport queue at midnight. Then they might realise not only what ‘passport power’ really is, but also what it is to stand as a senior member of the great European family.

Share

Alexander Francis Shaw

Journalist | Sailor